Table of Contents

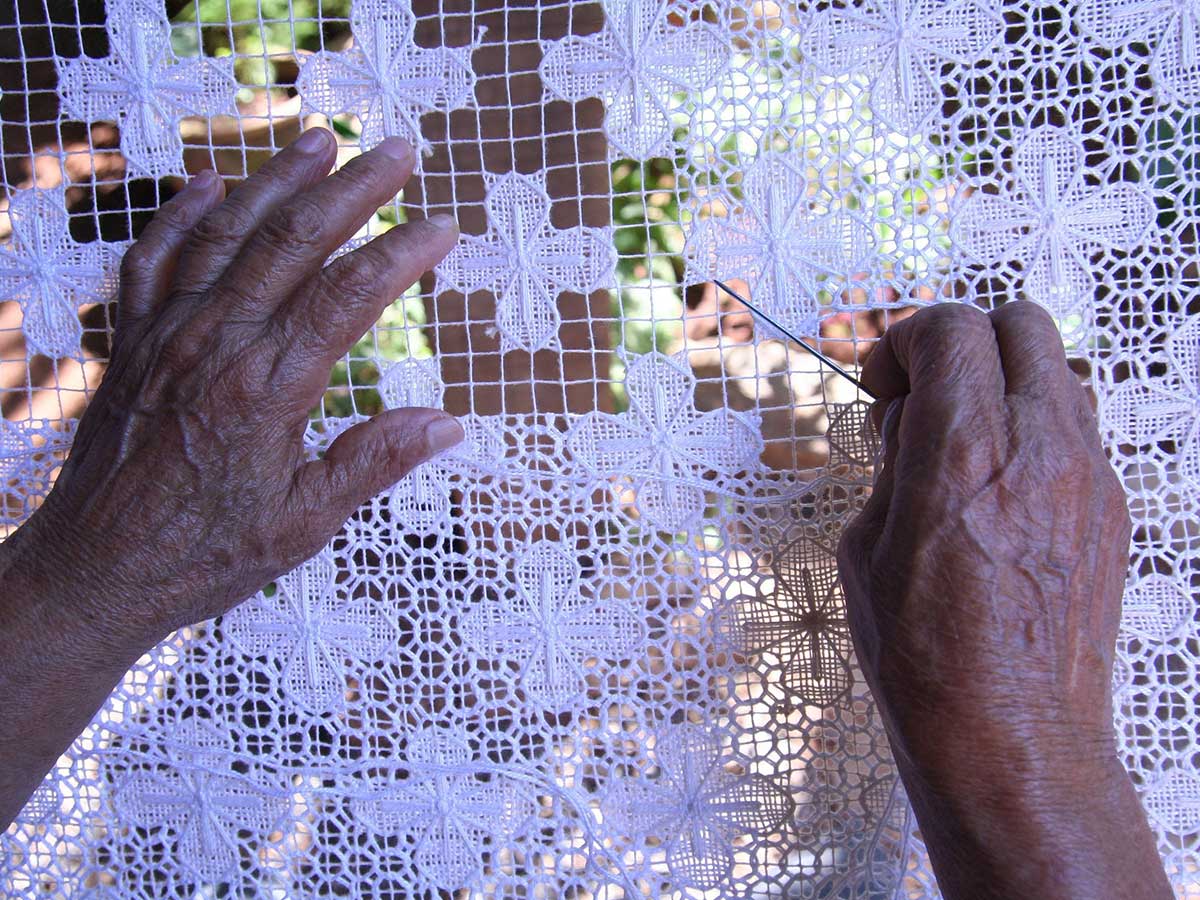

In dimly lit rooms smelling of lavender and aged fabric, elderly hands guide needles through linen with practiced precision. Each stitch follows patterns memorized decades ago, learned from mothers and grandmothers in unbroken chains stretching back centuries. Corfu’s embroidery tradition, though fading, persists in these dedicated practitioners whose work preserves cultural heritage as tangible and beautiful as any monument or manuscript.

The Art of Corfu Embroidery: Traditional Needlework Techniques

Embroidery arrived in Corfu through multiple cultural channels across centuries. Byzantine traditions established early foundations, ecclesiastical textiles requiring skilled needlework for liturgical purposes. These religious commissions maintained embroidery skills while establishing aesthetic standards and technical repertoires. Venetian rule brought Western European influences. Venetian nobility and wealthy merchants commissioned elaborate household linens demonstrating status through display textiles. Pattern books circulating from Italy introduced motifs and techniques that Corfiot needleworkers adapted to local tastes and traditions.

Ottoman influences filtered through trade contacts and mainland Greek connections. Eastern Mediterranean embroidery traditions, though from cultures Venetian Corfu often opposed militarily, nonetheless contributed aesthetic elements. Certain color combinations, pattern arrangements, and stylistic approaches reflect this complex cultural interchange.

The resulting synthesis created distinctively Corfiot embroidery styles recognizable to expert eyes. These traditions combined imported elements with local innovations, techniques passed through generations while evolving subtly. Regional variations existed between villages, families developing signature approaches identifying their work to knowledgeable observers.

Social class influenced embroidery complexity and materials. Wealthy families commissioned elaborate pieces using expensive threads including silk and metallic gold and silver. Common households produced simpler work using available materials, their pieces no less skillfully executed though less ostentatious in material cost.

Techniques and Materials

Corfu embroidery employed diverse techniques, each suited to particular effects and applications. Cross stitch, perhaps most widely practiced, created geometric patterns and stylized figures through colored thread counted against fabric weave. This technique’s relative simplicity made it accessible to less experienced needleworkers while allowing sophisticated designs.

Satin stitch produced smooth, lustrous surfaces covering fabric completely with parallel stitches. This technique suited floral motifs and curved shapes, the thread’s direction creating subtle shading effects. Skilled workers varied stitch length and angle achieving remarkable naturalism despite medium’s inherent flatness.

Pulled thread work created lacy effects by tightening stitches to draw fabric threads together, creating deliberate holes and openwork areas. This delicate technique required fine fabric and thread with careful tension control. The resulting textiles combined opacity and transparency creating elegant visual effects. Cutwork removed fabric areas entirely, edges then reinforced with buttonhole stitching preventing fraying. This technique, related to Italian reticella, produced bold geometric patterns contrasting solid and void. Corfu cutwork displayed particular refinement, tiny bars crossing open areas supporting elaborate patterns.

Gold thread embroidery represented highest expression of needlework art. Metallic threads couched onto fabric surfaces created glittering effects for ecclesiastical textiles and aristocratic commission pieces. This work demanded supreme skill, the threads requiring special handling techniques distinct from ordinary needlework. Fabric choices reflected both practical considerations and aesthetic preferences. Linen, produced locally from flax cultivation, provided primary ground fabric. Its strength, durability, and ability to withstand repeated washing made it ideal for household textiles receiving hard use. Cotton gradually supplemented and partially replaced linen as imported cotton became more available and affordable.

Thread colors followed both fashion and symbolism. White on white embroidery created subtle elegance suitable for fine linens. Colored work, using silk or cotton threads, ranged from restrained two color schemes to polychrome extravaganzas displaying full rainbow spectrums. Red held particular significance in traditional work, appearing prominently in many regional styles.

Motifs and Patterns

Floral designs dominated Corfu embroidery. Roses, carnations, lilies, and various stylized blooms covered textiles in profusion. These flowers, rendered with varying degrees of naturalism, reflected both decorative appeal and symbolic associations. Certain flowers carried specific meanings relating to virtues, lifecycle events, or religious significance.

Geometric patterns provided structure and framing. Borders featured repeating angular motifs creating visual boundaries and organizing decorated surfaces. These geometric elements balanced floral exuberance with ordered regularity, the interplay between organic and geometric creating visual interest.

Birds appeared frequently, particularly peacocks and doves. These creatures carried symbolic weight, peacocks representing immortality while doves symbolized peace and the Holy Spirit. Their decorative appeal complemented symbolic functions, elaborate tail feathers providing opportunities for needlework virtuosity.

Architectural elements including columns, arches, and stylized buildings occasionally appeared, particularly in ecclesiastical textiles. These motifs reflected Venetian architectural influences visible throughout Corfu’s built environment, translating stone into thread.

Human figures, though less common than flora and fauna, decorated certain pieces. Religious figures appeared on ecclesiastical textiles while secular scenes adorned domestic pieces. Stylization prevailed over naturalism, figures recognizable by attributes and context rather than realistic portraiture.

Pattern transmission occurred through multiple channels. Printed pattern books, imported from Italy, provided designs that needleworkers copied or adapted. Drawn patterns on paper transferred to fabric through various methods. Existing embroideries served as templates, motifs copied from admired pieces. Memory and improvisation allowed skilled workers creating designs spontaneously, drawing on internalized repertoires of motifs and compositional principles.

Social and Cultural Contexts

Embroidery played crucial roles in women’s lives and social relationships. Girls learned needlework from earliest ages, progressing from simple stitches to complex techniques as skills developed. Competence in embroidery represented essential feminine accomplishment, part of education preparing girls for household management and domestic responsibilities.

Dowry preparation consumed countless hours. Young women embroidered household linens over years preceding marriage, accumulating trousseau demonstrating skills and providing practical household goods. The quantity and quality of embroidered items indicated family status and bride’s accomplishments, these textiles inspected and evaluated by prospective in laws.

Communal needlework sessions provided social opportunities. Women gathered to sew collectively, their hands busy while conversation flowed. These gatherings reinforced community bonds while facilitating information exchange, news spreading through social networks during embroidery sessions. Young women learned from elders, skills and stories transmitted simultaneously.

Embroidery marked lifecycle events. Birth gifts included embroidered baby clothes and bedding. Wedding ceremonies featured elaborate textile displays. Death brought embroidered funeral cloths. These textiles commemorated transitions while demonstrating affection and respect through invested labor.

Economic dimensions complicated embroidery’s primarily social and cultural functions. Professional embroiderers, usually urban women, produced commissioned work for wealthy clients. This commercial embroidery provided income though generally carried lower status than amateur work for household use. The distinction between hobby and profession marked class boundaries, upper class women embroidering for pleasure while lower class women sewed from economic necessity.

Ecclesiastical Embroidery

Church textiles represented embroidery art’s pinnacle. Altar cloths, priest vestments, icon covers, and liturgical textiles required supreme skill and finest materials. These pieces, created for divine service, warranted effort and expense beyond secular embroidery. Orthodox liturgical requirements specified certain textiles and decorative programs. Vestment embroidery followed prescribed patterns reflecting theological symbolism. Colors corresponded to church calendar, different seasons requiring specific hues. This liturgical context gave embroidery spiritual significance beyond aesthetic appeal.

Wealthy families commissioned ecclesiastical embroidery as pious donations. These gifts demonstrated devotion while displaying family status. Donor inscriptions and heraldic elements identified benefactors, ensuring remembrance during services using donated textiles. This practice created incentive for exceptional quality work, families’ reputations attached to pieces’ beauty and durability.

Convents maintained embroidery workshops producing ecclesiastical textiles. Nuns dedicated to religious life possessed time and motivation creating elaborate pieces. Convent embroidery achieved remarkable quality, representing institutional investment and individual devotion combined.

The Orthodox tradition of venerating icons extended to embroidered icon covers. These textiles, decorated with religious imagery and precious materials, protected painted icons while adding decorative layers. Worshippers donated embroidered covers expressing devotion and gratitude for answered prayers.

Decline and Transformation

The 20th century brought dramatic changes undermining traditional embroidery. Mass produced textiles provided cheaper alternatives to hand embroidered linens. Ready made goods reduced household textile production across all crafts, embroidery included. Time consuming needlework seemed unnecessary luxury when factory made alternatives cost less and required no labor.

Education system changes reduced embroidery instruction. Traditional emphasis on needlework as essential feminine skill diminished as educational priorities shifted. Fewer girls learned techniques thoroughly, breaking generational transmission chains. By late 20th century, comprehensive embroidery skills survived primarily in oldest generation.

Lifestyle changes reduced contexts for embroidery display. Formal dining occasions featuring elaborate table linens decreased. Dowry customs weakened. The social importance of embroidered household textiles declined, removing motivation for learning and practicing skills requiring significant time investment.

Economic transformation drew women into paid employment. Time spent embroidering no longer seemed practical use of leisure hours when incomes allowed purchasing household textiles while jobs provided financial independence traditional domestic skills never offered. Embroidery became hobby rather than expectation.

Tourism initially seemed potential salvation for traditional crafts. Visitors purchased embroidered items as souvenirs, creating market for traditional work. However, this market often encouraged simplified designs requiring less skill and time, gradually degrading rather than preserving traditional techniques.

Contemporary Practice and Revival

Surviving practitioners, mostly elderly, continue traditional embroidery from personal commitment rather than economic necessity. These women embroider for pleasure, satisfaction, and cultural preservation. Their work maintains living connection to traditions that otherwise would exist only in museums and photographs.

Cultural organizations recognize embroidery’s heritage value. Programs documenting techniques record processes before knowledge disappears. Exhibitions display historical pieces educating public about traditional crafts. These initiatives raise awareness though translating appreciation into active practice proves challenging.

Workshops introducing traditional techniques to younger generations show modest success. Some young women discover embroidery appeal, appreciating handwork’s meditative qualities and creative satisfactions. These revival efforts, while not restoring embroidery to former centrality, prevent complete disappearance.

Contemporary artisans sometimes incorporate traditional techniques in modern contexts. Art textiles employing traditional methods create works for gallery display rather than household use. This artistic appropriation maintains techniques while transforming contexts and meanings.

Online communities connect embroidery enthusiasts globally. Corfiot embroiderers share knowledge through digital platforms, teaching techniques that once transferred only through personal contact. This democratization broadens access while altering traditional apprenticeship relationships.

Museums preserve outstanding historical examples. The Folk Museum and private collections maintain pieces demonstrating traditional embroidery at its finest. These textiles provide study resources and inspiration, tangible evidence of skills and aesthetic sensibilities characterizing earlier generations.

Economic and Practical Challenges

Revival efforts face significant obstacles. Quality traditional embroidery requires years developing skills. The time investment producing single piece means labor costs exceed what most purchasers willingly pay. This economic reality makes professional traditional embroidery essentially unviable.

Authentic materials grow difficult obtaining. Traditional linen fabric and threads meeting historical quality standards cost significantly more than modern alternatives. Substituting contemporary materials changes results subtly but meaningfully, the textiles feeling different despite similar appearance.

Pattern availability presents challenges. Historical pieces exist primarily in museums and private collections where access for study and copying faces restrictions. Published pattern books covering Corfu specific traditions remain scarce. Reconstructing traditional designs requires extensive research and often educated guessing.

Market confusion between authentic traditional work and tourist kitsch devalues genuine pieces. Mass produced imitations flood markets, their superficial resemblance to traditional embroidery confusing unsophisticated buyers. This competition makes marketing authentic work difficult and undercuts prices artisans might otherwise achieve.

Teaching traditional skills requires committed instructors and dedicated students. Finding both simultaneously proves difficult. The scattered nature of remaining knowledge, held by isolated individuals rather than organized schools, complicates systematic instruction.

Cultural Significance and Future Prospects

Corfu embroidery represents more than decorative needlework. These textiles embody cultural memory, aesthetic sensibilities, and social practices defining earlier generations’ lives. Each piece contains accumulated hours of labor, creativity, and skill, making them valuable cultural artifacts regardless of utilitarian function.

The gendered nature of embroidery tradition raises interesting questions. This craft, exclusively female domain, preserved and transmitted women’s knowledge, creativity, and values. Embroidered pieces document women’s lives and perspectives often absent from written historical records. Their study illuminates social history otherwise invisible.

Embroidery’s decline parallels broader cultural transformation. Traditional skills vanishing reflect changed lifestyles and values, not simply laziness or cultural degradation. Contemporary life offers different satisfactions and challenges than those faced by women spending hours embroidering dowry linens. Understanding this context prevents simplistic nostalgia while acknowledging genuine losses.

Future prospects remain uncertain. Complete disappearance seems unlikely, committed individuals will preserve techniques regardless of broader cultural marginalization. Whether embroidery remains purely historical curiosity or experiences genuine revival depends on factors including economic viability, educational programs, and cultural values emphasizing traditional crafts.

Perhaps most realistically, traditional embroidery may survive in transformed state, techniques adapted to contemporary contexts and aesthetics. This evolution, while changing traditional forms, maintains needlework skills and cultural continuity. Living traditions always evolve; the alternative is museum preservation of dead practice.

The needles still move through fabric in a few Corfiot households. Thread patterns emerge stitch by stitch, ancient designs taking shape through practiced movements. These contemporary practitioners, whether elderly women continuing lifelong practice or young enthusiasts discovering traditional techniques, keep alive craft connecting present to past through unbroken thread running across generations. Their work honors ancestors while creating beauty enriching contemporary life, demonstrating traditional craft’s enduring value in modern world.